Ukraine & the Energy Transition

Ukraine & the Energy Transition

Some will tell you that the dependence on hydrocarbons from outlaw or unstable “Petrostates” is a cautionary tale reflecting the need for the U.S. to pump more oil and natural gas to lower prices both here and abroad. Others will say that current high energy prices, largely driven by Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, are a cautionary tale indicating the need to get on with the transition to non-emitting resources.

Both sides are right.

Our economy, and those of our allies, will need hydrocarbons for years to come. Our climate concerns indicate an urgent need to make the transition to a low carbon power structure that electrifies the economy. We can argue about whether this means advanced modular nuclear power, or some other power sources that are available 24/7 to back up renewable power and batteries. But a reliable grid is the foundation of a functioning society and will be at the center of a successful transition to a clean power sector for the rest of the new, clean economy.

Considered Haste…

Proponents of renewables will argue – correctly – that our economic exposure to Russian instability would be minimized if we were further along in the energy transition. But regulators and policy makers can not merely direct the transition to happen now. Decisions made today to balance low or zero carbon resources must consider the need for reliability to help the transportation industry and other sectors of the economy make the transition. We can’t make the same fatal mistake that Germany made, for instance, to shutter its nuclear power stations in reaction to the Fukushima nuclear incident in Japan in 2011. That decision, in addition to relying on more emitting resources like coal and natural gas, led to Germany’s increased dependency on Russian natural gas.

Continued movement to renewable energy, storage and new technologies such as “green hydrogen” and new modular nuclear units is the urgent order of the day in the U.S, and the West. But while we want it to happen quickly, it must be thoughtfully achieved. Let’s call the effort “considered haste”.

Rise of the “electrostates?”

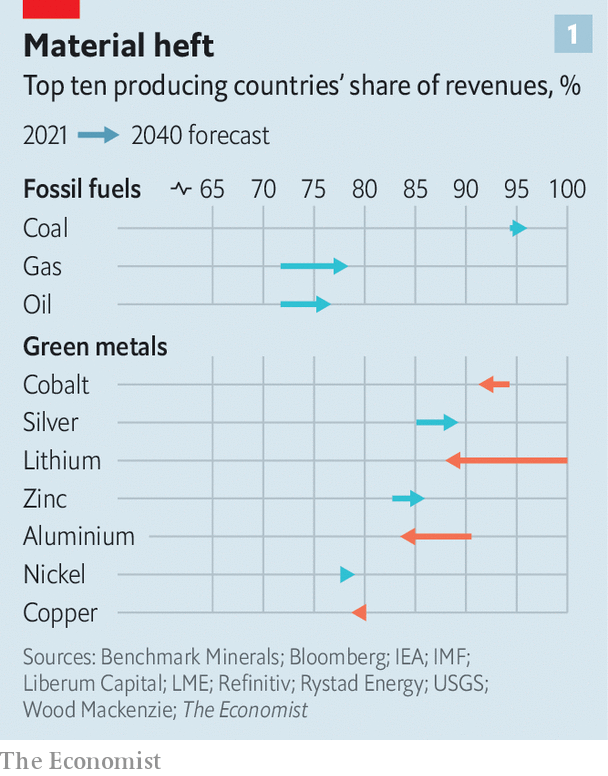

An article in the last issue of The Economist made the point that while the West – and all the world – needs to get on with the energy transition, there are risks that will emerge from this new future. Nickel, lithium, copper and more exotic materials needed for new clean technologies will come from many places around the world. Some, like Australia, are positioned in terms of economic structures and law to handle them well. But many less developed countries like Congo, Guinea and Mongolia are not. In places like these, the huge cash infusion – The Economist estimates at perhaps $1 trillion per year by 2040 – will likely lead to corruption, which will lead to instability, which may lead to supply chain disruptions.

This leads to second point that often goes unrecognized by those who think the U.S. would be fine right now if only we’d just drill more of our own oil. Both hydrocarbons and the new exotic materials needed for the electric future are fungible resources, the cost of which are reflected in supply and demand forces of global markets. Prices for hydrocarbons are a function of global supply which can be disrupted by events like a pipeline accident in Central Asia (last week) or Russian sanctions, just as global demand can be affected by the retreat of a Pandemic like Covid. The same will be true of the dependency of the new “electrostates”.

The key is to diversify sources to the extent possible. Global prices, reflecting the availability of resources, will inform investments in clean energy and thus create incentives for companies to diversify supply chains or seek new production technologies and sources. Markets will be essential to efficiently meeting the needs of the energy transition.

Final points for my neighborhood.

My “neighborhood” is the Western U.S. We are arguably taking more aggressive measures toward the energy transition than any other “neighborhood.” Efficiently and reliably doing so has driven many in the Western Power sector to strive for an integrated Western Power Market. But as we do this, policy makers and regulators should keep two points in mind.

- Prices to produce electricity this summer in the West may be very high. Natural Gas prices are as high as they have been in a decade, reflecting the global demand for the stuff. Availability of hydro power may be low again this summer as precipitation in most areas of the West has disappointed yet again. A hot summer, in conjunction with a grid that is not optimized to move power efficiently across the whole region, could result in volatile prices or worse. But the prices are necessary to inform policy makers of the needs.

- The transformation will happen, but in the near term it may require some natural gas resources to balance the grid. As renewable energy that has near-zero marginal costs crowds out natural gas from the revenue of the energy market, how will the necessary natural gas resources be compensated for being there to balance the grid?

These are hard questions that are made more apparent by the instability of energy markets wrought by Russia’s naked aggression. As we ponder these issues, let me whisper a prayer for those in the Ukraine who aren’t just inconvenienced by high energy prices, but who are giving us a lesson in bravery and the true cost of freedom.